CAP antibiotics

- Outpatient:

- Healthy: amoxicillin || doxycycline || macrolide

- comorbidities: oral b-lactam plus macrolide/doxy || respiratory fluoroquinolone

- Inpatient: IV b-lactam plus macrolide || respiratory fluoroquinolone

- ICU: IV b-lactam plus macrolide || B-lactam plus respiratory fluoroquinolone

- risk of pseudomonas: antipseudomonal b-lactam plus macrolide || quinolone

- risk of MRSA: standard therapy plus vancomycin/linezolid

- Consider systemic corticosteroids if severe

- Duration

- Outpatient: 5 days. 1-3 days azithro due to long half life

- Inpatient: 5-7 days

- Follow up

- Outpatient: 10-14 days

- Inpatient

- Switch from IV to oral when sx improve, afebrile on 2 occasions 8 hours apart, tolerating PO. 24-48 hrs

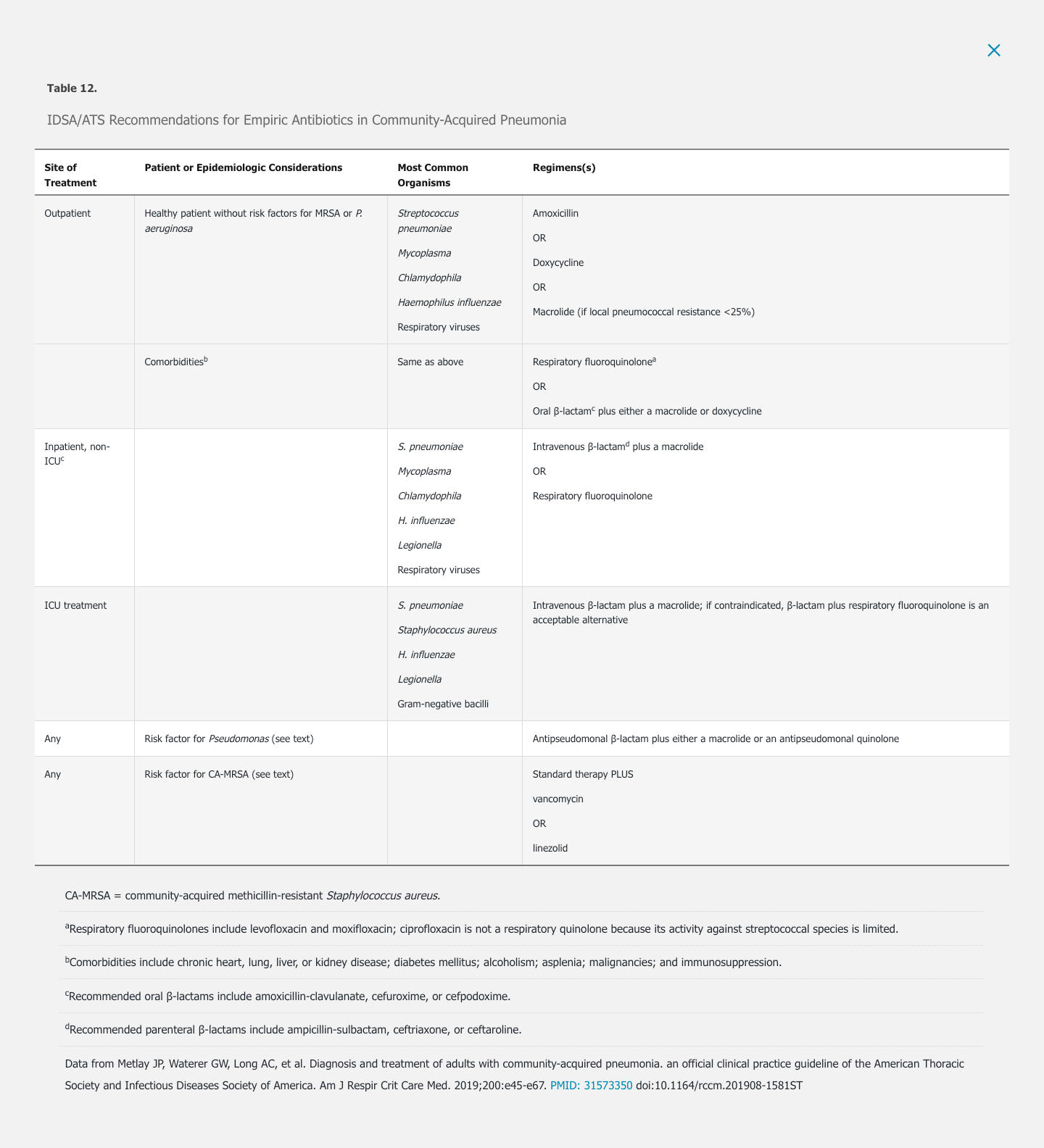

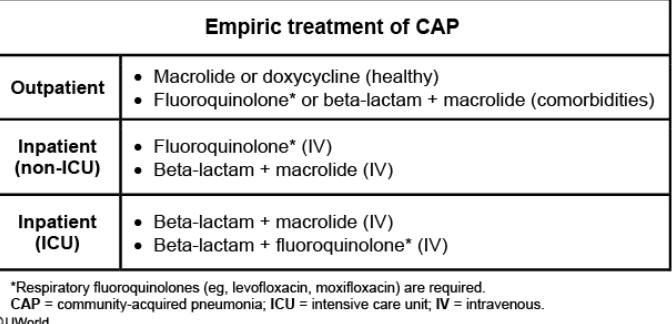

Ambulatory empiric therapy for CAP is directed against S. pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, and atypical bacteria, even though a significant proportion of patients with CAP infected with viral pathogens do not benefit from antibiotic therapy. In otherwise healthy patients, regimens include monotherapy with amoxicillin, doxycycline, or a macrolide (either azithromycin or clarithromycin if pneumococcal resistance to macrolides is less than 25%).

For patients with significant comorbidities treated as outpatients, a respiratory quinolone or a β-lactam plus a macrolide is recommended. Macrolides and quinolones may prolong the QT interval and alternative agents should be considered in patients at risk for torsades de pointes, including history of a long QT interval; taking other medications that can prolong the QT interval; and with electrolyte abnormalities. When macrolides and quinolones are contraindicated, doxycycline can be substituted for a macrolide and given in conjunction with a β-lactam.

Patients with more severe infections requiring hospitalization may be infected with a broader spectrum of bacterial pathogens, reflecting host susceptibility and organism virulence. Recommended empiric regimens include a parenteral β-lactam agent (a third-generation cephalosporin or ampicillin-sulbactam) plus a macrolide or a respiratory fluoroquinolone (see Table 12). Use of ampicillin-sulbactam or other penicillin-based antibiotics offers the advantage of increased anaerobic spectrum and should be considered if lung abscess or empyema is suspected. For patients allergic to β-lactams or those treated with a component of this regimen in the preceding 3 months, monotherapy with a respiratory quinolone is appropriate.

An area of controversy is whether empiric therapy for atypical bacterial infection confers an outcome advantage among hospitalized patients with CAP who do not require ICU care. The CAP-START study, a randomized controlled trial published in 2015, evaluated the two currently recommended regimens (a β-lactam plus a macrolide or a respiratory quinolone) compared with β-lactam monotherapy in this population and found no significant difference in outcomes among the three groups. This result was not replicated in a second randomized trial or in several observational studies that found excess mortality associated with β-lactam monotherapy compared with standard therapy. Furthermore, several studies have shown a survival benefit for patients with bacteremic CAP caused by S. pneumoniae treated with combination β-lactam plus macrolide therapy; whether this benefit reflects a direct antimicrobial effect or the anti-inflammatory properties of azithromycin is uncertain.

The microbiology among patients with CAP requiring ICU care is shown in Table 12. In this population, monotherapy with a respiratory quinolone is contraindicated. Suggested regimens include coadministration of a parenteral β-lactam active against S. pneumoniae and a second agent active against Legionella species (either azithromycin or a quinolone). For patients with a history of immediate hypersensitivity reaction to β-lactam antibiotics, aztreonam, which is purely active against gram-negative bacteria, is an acceptable alternative if given with a respiratory quinolone to treat S. pneumoniae and atypical organisms.

MRSA is not adequately treated by the previously discussed empiric regimens, yet is increasingly recognized as causing CAP, particularly in critically ill patients. CAP caused by MRSA is associated with preceding influenza infection and injection drug use, although it may present in patients without any identifiable risk factors. Empiric therapy for MRSA should be considered in patients with one of these risk factors, a suspicious Gram stain (gram-positive cocci in clusters), conventional therapy failure, pleural-based lung nodules (suggesting septic pulmonary emboli), or cavitary lung lesions. Optimal treatment for MRSA CAP has not been defined, but options include vancomycin, linezolid, and ceftaroline. Notably, daptomycin binds to surfactant, resulting in negligible alveolar levels, and is therefore not effective in pulmonary infections.

P. aeruginosa, a significant cause of HAP, can also cause CAP and is not adequately treated by standard empiric regimens. Pseudomonas should be considered in immunocompromised patients and in patients with underlying structural lung disease (bronchiectasis or cystic fibrosis) or medical conditions requiring repeated courses of antibiotics. When clinical concern for Pseudomonas is present, initial empiric therapy with two active agents is indicated. Options include an antipseudomonal β-lactam (piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, or meropenem) in conjunction with either a quinolone (levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin) or an aminoglycoside. If an aminoglycoside is chosen, a macrolide should be added for empiric coverage of atypical bacteria. Moxifloxacin, a respiratory quinolone with activity against S. pneumoniae, is relatively ineffective against Pseudomonas and should not be used for treatment when Pseudomonas is a concern. Inclusion of a quinolone in the empiric regimen is relatively contraindicated in patients who did not respond to previous courses of this drug.

Controversy exists over optimal management of hospitalized patients with CAP and a positive rapid viral test result. Although respiratory viruses may cause severe CAP, a viral cause does not exclude a bacterial coinfection. S. aureus, S. pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pyogenes have all been associated with postinfluenza necrotizing CAP. Therefore, IDSA/ATS guidelines recommend continuing antibiotics for CAP even when a viral pathogen is identified. For all hospitalized patients also diagnosed with influenza, oseltamivir should be prescribed, regardless of the duration of illness.

For patients with uncomplicated CAP who demonstrate clinical improvement (demonstrated by resolution of vital sign abnormalities, ability to eat, normal mentation) over the first 3 days, a 5-day course of therapy is adequate for cure. Exceptions include patients with cavitary disease or lung abscess, empyema, concomitant bacteremia, extrapulmonary infection, or ongoing instability, defined as persistent fever, abnormal vital signs, or hypoxia. Many authorities also recommend prolonged duration of antibiotics (at least 14 days) for CAP caused by S. aureus or Enterobacteriaceae; fungal or mycobacterial lung infections may require a more prolonged course of treatment.

Empiric intravenous antibiotics with an anti-pneumococcal beta lactam (eg, ceftriaxone) and an advanced macrolide (eg, azithromycin) or a respiratory fluoroquinolone (eg, levofloxacin). This provides coverage for the most common typical (eg, Streptococcus pneumoniae) and atypical (eg, Legionella) CAP organisms.